Scientists from Imperial College London and Kumamoto University, Japan, have discovered how the human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) is able to cause leukemia in some people, pointing the way to developing better therapies or cancer prevention strategies for patients in this group.

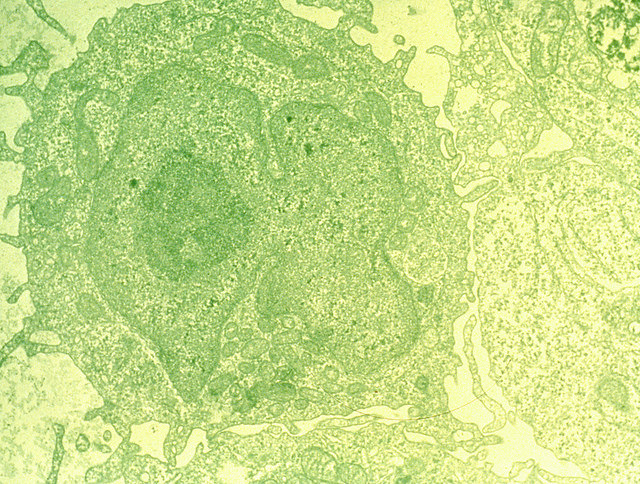

The researchers use single-cell analysis to show how the virus activates T lymphocytes excessively causing them to turn cancerous. Their results are published in an article in The Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Decades after being initially infected by HTLV-1, nearly five percent of infected people develop ATL. HTLV-1 only infects T cells and transforms them into leukemia cells, but the prolonged time between viral infection and the initiation of malignancy has made it difficult to determine how this transformation occurs.

Like other forms of cancer, the progression of ATL can be slow or aggressive but there is no standard treatment for advanced ATL. Moreover, this rare form of leukemia has a high rate of recurrence after conventional treatment options such as chemotherapy and antiviral treatments. The virus hijacks the activation machinery of T cells inducing a high level of activation until the T cells become malignant.

Yorifumi Satou, PhD, professor of virology at Kumamoto University and co-first author of the paper says, “While only a small percentage of people with HTLV-1 viral infections go on to develop adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma, there are estimated to be around five to ten million carriers of the virus worldwide, and in some areas it is endemic—for example there are around one million cases in Japan.”

Immunologist and cell biologist Masahiro Ono, PhD, professor at the department of life sciences at Imperial and co-first author of the paper says, “There is therefore a great need to understand how the virus turns our T-cells against us in the progression to cancer. Our work highlights a key mechanism for this change and provides us with new directions to search for ways to interfere with the process, potentially preventing the cancer from developing.”

Ono adds, “Our study shows that the virus infection induces overactivation of infected T-cells, which may provide the virus opportunities to replicate themselves, while making the infected T-cells vulnerable to cancer-causing mutations. To understand how the virus causes the cancer is a very important step for developing new treatments for the virus-induced leukemia patients.

Leukemias are cancers of the blood or bone marrow and are characterized by an abnormal increase in the number of white blood cells. T cells are a type of white blood cells that play an important role in fighting off pathogens like viruses and bacteria.

The HTLV-1 virus homes into a subtype of T cells and persists in these cells in a latent state without releasing new virus particles or causing any ill effects. In most people who carry HTLV-1 the virus remains in the latent state for the lifetime of the individual but in around five per cent of carriers the virus reawakens after decades of dormancy and affects the activity of the host’s T-cells.

“HTLV-1 is a virus similar to HIV, specifically infecting T-cells only, but does not cause immunosuppression. Instead, HTLV-1 infection leads to leukemia in a small percentage of HTLV-infected people,” says Ono.

In the current study the researchers sequenced RNA from over 87,000 T cells to compare gene expression in virus-free donors, healthy carriers of the virus, and patients with ATL, to understand how the virus interacts with T-cells in these different groups.

“Single-cell RNA sequencing was used to analyze activities of all genes in tens of thousands of cells, which allows a full characterization of T-cells that are in transition to cancer cells and how the cancer (leukemia ) progresses,” says Ono.

The results reveal that HTLV-1 causes T cells to over-produce proteins needed for cell proliferation in infected people who develop ATL. This hyper-proliferative and hyperactive state causes these aberrant T cells to avoid regulatory immune signals that remove malfunctional cells. The researchers suspect these changes in gene expression also make T cells more vulnerable to DNA damage, such as damage induced by chemicals or radiation, speeding up their change into a malignant state.

Ono says, “The chronic activation of T-cells could be halted by molecules that block signaling pathways that tell the cells to activate. Alternatively, treatments could target the proteins activated T-cells create to help them proliferate.”

Exploring these processes could lay the foundations for new treatment options for this rare form of cancer. The team is currently working to develop a new method to halt the overactivation of T-cells to stop the development of leukemia in HTLV-1 infected T cells.