A collaboration between the labs of Alessandro Sette, Dr. Biol. Sci., professor in the Center for Infectious Disease and Vaccine Research, and Shane Crotty, PhD, professor at La Jolla Institute for Immunology, is starting to fill in the massive knowledge gap and is providing the first cellular immunology data from patients who have recovered from COVID-19.

Their work, published in Cell in a paper titled, “Targets of T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus in humans with COVID-19 disease and unexposed individuals,” studied T cell and antibody immune responses in average COVID-19 cases.

The study documents a robust antiviral immune response to SARS-CoV-2 in a group of 20 adults who had recovered from COVID-19. The findings show that the body’s immune system is able to recognize SARS-CoV-2 in many ways, dispelling fears that the virus may elude ongoing efforts to create an effective vaccine.

They also showed that 100% of COVID-19 cases made antibodies and CD4 T cells. Also, 70% of COVID-19 cases made measurable CD8 T cells. “Our data show that the virus induces what you would expect from a typical, successful antiviral response,” said Crotty.

They also found CD4+ T-cell responses to spike, the main target of most vaccine efforts, were robust, and correlated with the magnitude of the anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG and IgA titers.

“If we had seen only marginal immune responses, we would have been concerned,” said Sette, and added, “but what we see is a very robust T-cell response against the spike protein, which is the target of most ongoing COVID-19 efforts, as well as other viral proteins.”

“All efforts to predict the best vaccine candidates and fine-tune pandemic control measures hinge on understanding the immune response to the virus,” said Crotty, also a professor in the Center for Infectious Disease and Vaccine Research. “People were really worried that COVID-19 doesn’t induce immunity, and reports about people getting re-infected reinforced these concerns, but knowing now that the average person makes a solid immune response should largely put those concerns to rest.”

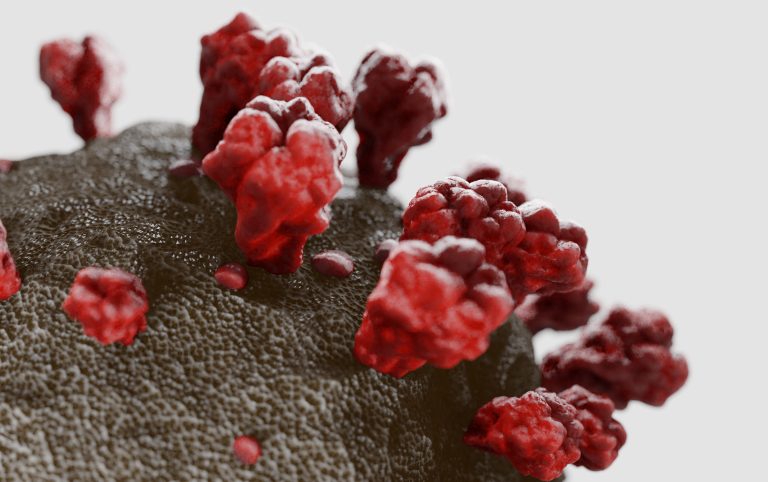

In an earlier study, Sette and his team had used bioinformatics tools to predict which fragments of SARS-CoV-2 are capable of activating human T cells. The scientists then, in this latest research, tested whether T cells isolated from adults who had recovered from COVID-19 without major problems, recognized the predicted protein fragments, or so-called peptides, from the virus itself. The scientists pooled the peptides into two big groups: The first so-called mega-pool included peptides covering all proteins in the viral genome apart from SARS-CoV-2’s “spike” protein. The second mega-pool specifically focused on the spike protein that dots the surface of the virus, since almost all of the vaccines under development right now target this coronavirus spike protein.

“We specifically chose to study people who had a normal disease course and didn’t require hospitalization to provide a solid benchmark for what a normal immune response looks like, since the virus can do some very unusual things in some people,” said Sette.

The teams also looked at the T-cell response in blood samples that had been collected between 2015 and 2018, before SARS-CoV-2 started circulating. They detected SARS-CoV-2-reactive CD4+ T cells in ~50% of unexposed individuals. But everybody has almost certainly seen at least three of the four common cold coronaviruses, which could explain the observed crossreactivity.

Any potential for crossreactive immunity from other coronaviruses has been predicted by epidemiologists to have significant implications for the pandemic going forward. Crossreactive T cells are also relevant for vaccine development, as cross-reactive immunity could influence responsiveness to candidate vaccines.

Whether this immunity is relevant in influencing clinical outcomes is unknown, tweeted Crotty, but it is tempting to speculate that the crossreactive CD4+ T cells may be of value in protective immunity, based on SARS and flu data.

“Given the severity of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, any degree of cross-reactive coronavirus immunity could have a very substantial impact on the overall course of the pandemic and is a key detail to consider for epidemiologists as they try to scope out how severely COVID-19 will affect communities in the coming months,” said Crotty. It may explain why some people or geographical locations are hit harder by COVID-19.

And, although these results don’t preclude that the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 may be detrimental, they provide an important baseline against which individuals’ immune responses can be compared; or, as Sette likes to put it, “if you can get a picture of something, you can discuss whether you like it or not but if there’s no picture there’s nothing to discuss.”

“We have a solid starting foundation to now ask whether there’s a difference in the type of immune response in people who have severe outcomes and require hospitalization versus people who can recover at home or are even asymptomatic,” added Sette. “But not only that, we now have an important tool to determine whether the immune response in people who have received an experimental vaccine resembles what you would expect to see in a protective immune response to COVID-19, as opposed to an insufficient or detrimental response.”